You’d have to be on another planet or at least not in the UK to have missed that Britain’s cultural establishment has embarked on marking the 40th anniversary of the release a record called Anarchy in the UK by the Sex Pistols as the 40th ‘birthday’ of Punk Rock. The irony of Her Majesty’s Government endorsing, even canonising, a group that once snarled that the Queen “ain’t no human being” won’t be lost on many either. That attack on the monarchy came from the song No Future, in which the Pistols also proclaimed “There is no future in England’s dreaming”. In reality there turned out to be a very lucrative future for multi-millionaires John Lydon of the Sex Pistols and Vivienne Westwood, the doyenne of punk style, knighted a Dame by the aforementioned monarch.

Let’s face it though, the mainstreaming and disarming of transgression by cultural gatekeepers is nothing new and there’s no point in railing against it 30 years after the fact. What I want to do instead is take a broader look at the context in which punk emerged and its little talked about interactions with rebellion in other cultural quarters.

Punk emerged in London in the ’70s as a rejection of white English culture’s bourgeois moirés. It proposed values for a more accessible context for music making and art, embracing freedom of expression and a DIY ethic, reflecting the mood of a generation of white working class England. Reggae, in the black community, was punk’s counterpart. It also attracted a following from punk’s predecessors the skin heads, whose identity was ironically appropriated by neo-fascists. Reggae drew on traditions and experiences that were never part of the dominant culture and social order in England – or ‘Babylon’. Reggae grew rather than exploded like punk. Both cultures co-existed in working class inner cities. Reggae bands like Steel Pulse began to develop and lay claim to distinctly British interpretations of the Jamaican genre. They created a style that reflected the specificity of the black British experience, drawing on and embracing influences from Britain’s morphing of American Rock ’n Roll into Pop.

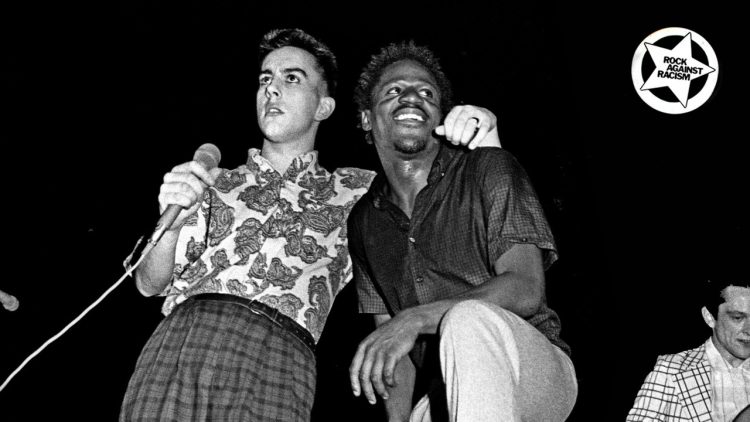

Punk and Reggae, or more chiefly its progenitor Ska, eventually came together in 2-Tone, via the momentous Rock Against Racism [RAR] events between 1976 and 1978. The RAR Carnival in 1978, bringing punk from bands like the Clash and reggae from Steel Pulse and others together on the same stage, is said to have sparked the 2-Tone movement. The best known exponents of which, like The Specials, The Selector, Madness, The Beat etc, were overtly anti-racist flag bearers for the RAR movement going forward.

Punk and Reggae, or more chiefly its progenitor Ska, eventually came together in 2-Tone, via the momentous Rock Against Racism [RAR] events between 1976 and 1978. The RAR Carnival in 1978, bringing punk from bands like the Clash and reggae from Steel Pulse and others together on the same stage, is said to have sparked the 2-Tone movement. The best known exponents of which, like The Specials, The Selector, Madness, The Beat etc, were overtly anti-racist flag bearers for the RAR movement going forward.

Punk seemed to celebrate a disdain for the hegemony of virtuosity, rejecting established notions of artistic excellence which were seen as a mechanism of disempowerment in the pre-digital age of music making when the attainment of virtuosity was all but denied to those without social or economic access to the means of instrumental training. Jazz, on the other hand, was supposed to be all about virtuosity – albeit developed by autodidacts from the excluded enclaves of black America before becoming embraced by a liberal cultural intelligentsia. But however much co-opted by the musical establishment, jazz was never a bourgeois art form. The expression ‘jazz’ is thought to have come from the slang word jasm meaning spirit, energy, vigour. It was also once a word used to describe things that can’t be defined, grasped or easily deciphered. Jazz began in New Orleans’ Congo Square during American slavery as coded expression, an act of cultural rebellion impenetrable by slave masters who congratulated themselves for the charitable act of giving their property a day off to indulge in their ‘primitive practices’.

Free jazz emerged in the late-50s/early-60s as both an acknowledgment of jazz’s roots and an unshackling of musical expression from the chains of Euro-centric rules of rhythm and harmony. These rules were viewed by free jazz exponents as a cultural manifestation of social and economic repression. Key progenitors of free jazz such as Ornette Coleman and Archie Shepp were later involved in the Black Arts Movement, which was philosophically aligned to the Black Power movement and figures and organisations like Malcolm X and the Black Panthers.

Free jazz emerged in the late-50s/early-60s as both an acknowledgment of jazz’s roots and an unshackling of musical expression from the chains of Euro-centric rules of rhythm and harmony. These rules were viewed by free jazz exponents as a cultural manifestation of social and economic repression. Key progenitors of free jazz such as Ornette Coleman and Archie Shepp were later involved in the Black Arts Movement, which was philosophically aligned to the Black Power movement and figures and organisations like Malcolm X and the Black Panthers.

So there are parallels to be drawn between the political drivers and associations of both punk and the free jazz movement of the 60s and early 70s. Artists from both scenes eventually sought each other out for musical collaborations and, in the UK, many jazz musicians played in punk bands. Saxophonist Lol Coxhill recorded with The Damned and multi-instrumentalist Steve Beresford regularly collaborated with all-female punk band The Slits. Both The Stranglers and The Clash had drummers – Jet Black and Topper Headon respectively – that had previously played in jazz bands.

This convergence raises the question of whether Punk’s musical aesthetic, emerging from a rejection of English bourgeois aesthetics, was more about accessibility and embracing freedom of expression than an outright rejection of virtuosity. Today a punk attitude permeates a wide range of often quite virtuosic music making. Bands like Acoustic Ladyland are overtly and self-proclaimed ‘punk-jazz’. Just hearing them reveals explicit expressionistic connections between punk and free jazz. Young Fathers bring a punk sensibility to Hip Hop, while Shabaka Hutchins’ jazz rooted virtuosity does anything but distract from the punk sensibility of The Comet Is Coming, which also references Sun Ra’s representation of Afrofuturism, itself forged in the fires of free jazz in the 60s.

Today, after the success of movements like RAR putting pay to attempts to divide working class communities along racial lines, contemporary black culture has come to dominate and define urban working class culture in the UK. Black artists’ appropriation of technology (chiefly in Dub and Hip Hop) has liberated music making from the elitist clutches of the conservertoire, major record labels and expensive recording studios, and has continued to generate new forms such as Jungle, Drum ‘n Bass and Dub Step. Black and white are now listening to and making the same music.

For decades popular music aligned itself with protest, social commentary, rebellion and dreamings of a better world through artists ranging from Curtis Mayfield, Marvin Gaye and Bob Marley through Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchel to the angrier voices of Punk and Hip Hop. Almost coinciding with Punk, Hip Hop rose up out of the rubble of an apocalyptic 70s Bronx in New York City as an alternative cultural vanguard for African-American and New York’s Latino youth before becoming almost subsumed by a pornographic commodification of poverty. For a long moment, from the ‘90s onwards, it seemed the agitational imperative was lost – at least in the mainstream. The so called “end of history” and post-modernism consigning overtly political rebellion through popular culture to the trash can of what Mark Fisher1 calls our “lost futures”.

However, similar sociopolitical conditions to those that prevailed in 1976 have re-materialised in post-Brexit Britain and a Trump led USA. Counter-posed is the emergence of new movements like Black Lives Matters and socialist challenges for the leadership of liberal and social democratic major political parties. The AfroPunk scene, which in America dates back to punk’s original heyday, has laid claim to the legacy of punk, free jazz and Afro Futurism. In the US mainstream music releases from the likes of A Tribe Called Quest, Kendrick Lamar, Common, Beyoncé and her sister Solange have ‘woke’ to draw a line in the sand, while in the UK the likes of Skepta, Stormzy and Akala are supporting Britain’s burgeoning Black Lives Matter movement and responding to the impact of austerity and post-Brexit xenophobia.

However, similar sociopolitical conditions to those that prevailed in 1976 have re-materialised in post-Brexit Britain and a Trump led USA. Counter-posed is the emergence of new movements like Black Lives Matters and socialist challenges for the leadership of liberal and social democratic major political parties. The AfroPunk scene, which in America dates back to punk’s original heyday, has laid claim to the legacy of punk, free jazz and Afro Futurism. In the US mainstream music releases from the likes of A Tribe Called Quest, Kendrick Lamar, Common, Beyoncé and her sister Solange have ‘woke’ to draw a line in the sand, while in the UK the likes of Skepta, Stormzy and Akala are supporting Britain’s burgeoning Black Lives Matter movement and responding to the impact of austerity and post-Brexit xenophobia.

All of this is taking place in the digital age – a period during which DIY culture has almost become the rule rather than the exception with accessible technology rendering the DIY aesthetic often indistinguishable from the mainstream. Cut-and-paste isn’t about photocopiers, glue and safety pins anymore. It’s about 24bit sampling in bedroom studios and on mobile devices while high-definition smart phone cameras and social media instantly expose the brutal transgressions of the forces of the state. Peer-to-peer platforms like Youtube have captured audiences from TV with music videos, that are becoming ever more politicised, being among the most watched content.

An important use we can make of these channels in these urgent times is to re-surface authentic and inclusive histories so that at a time when we most need unity, we can share and be informed by a more comprehensive understanding of the convergences that once took place.

1Since the original publication of this article, the author and cultural critic Mark Fisher sadly passed away. The hyperlinked mention of him in this article has since been changed to point to a tribute to him on this site.

Discussion

No comments yet.